A prime example of extraction capitalism

Why Eastern Morocco’s air is becoming unbreathable

Published: 2025-07-11 • Updated: 2025-07-12 • Topics: air-quality, moroccan sahara, storm • Status: finished • Confidence: factual

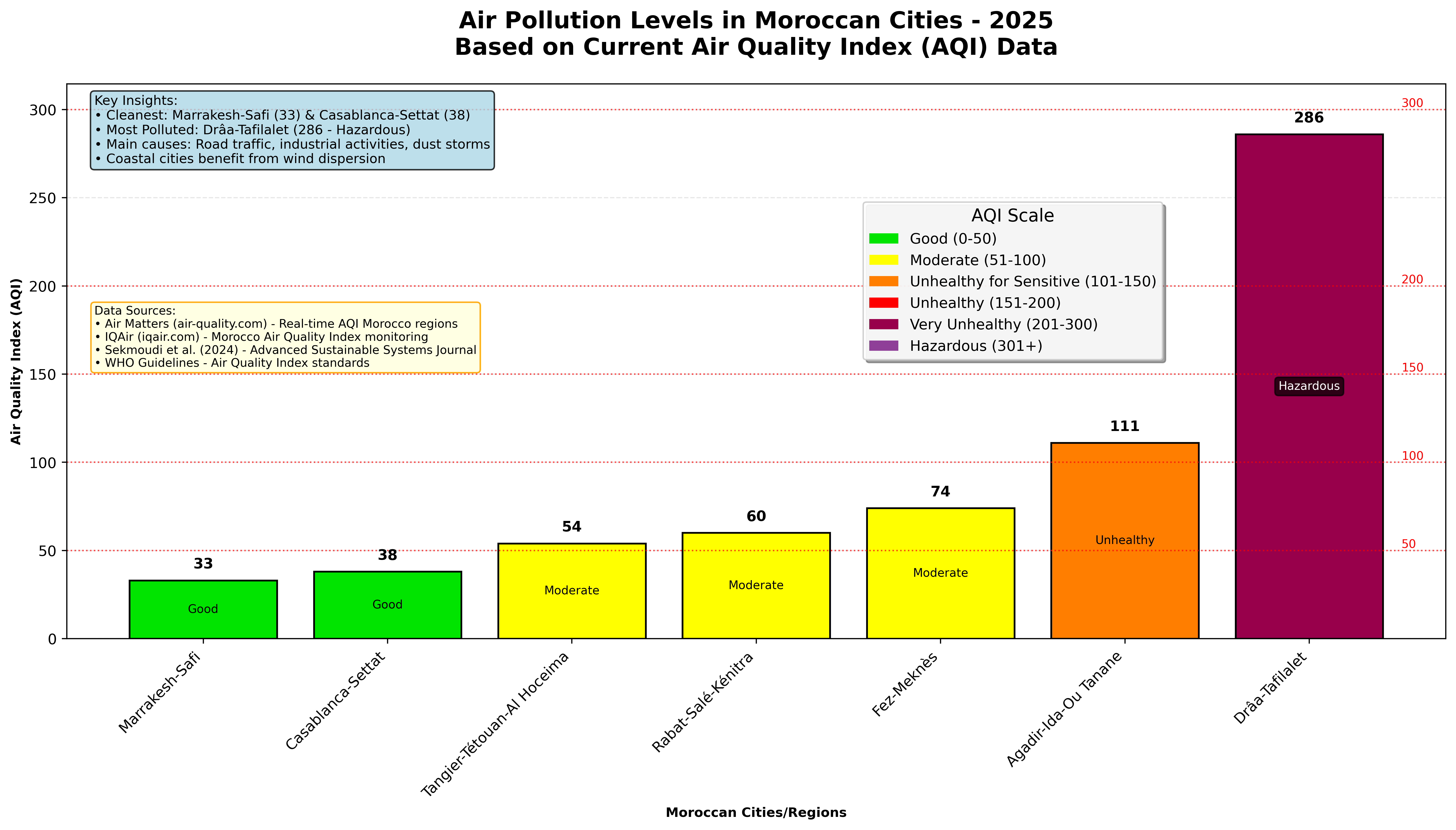

Which has worse air quality in Morocco - Casablanca with its 3.5 million people and industrial sprawl, or a sparsely populated desert region most tourists have never heard of? Well, you surely are in for a big surprise.

The Draa-Tafilalet region of eastern Morocco is experiencing an environmental catastrophe that reads like a textbook case of systems collapse. PM2.5 concentrations are currently running at 2.4 times the World Health Organization’s annual guidelines1, with Air Quality Index values consistently hitting the 60-64 range across cities like Goulmima, Mhamid, Zagora, and Ouarzazat2. But what makes this particularly fascinating from a systems perspective is how multiple seemingly unrelated factors have combined to create a feedback loop of environmental degradation that’s accelerating beyond anyone’s ability to control it.

To understand why this matters beyond Morocco’s borders, consider that the Draa-Tafilalet crisis represents a preview of what climate adaptation failure looks like in practice. This isn’t just another pollution story; it’s a real-time case study in how environmental, economic, and social systems can spiral into collapse even when everyone involved understands what’s happening.

The story begins with geography, but not in the way most environmental narratives do. The lower Draa Valley sits in an inland drainage basin in the Moroccan Sahara, essentially a natural dust collection point3. In geological terms, this region has always been what scientists call a “dust hotspot” - a place where atmospheric and topographical conditions naturally concentrate airborne particles. Under normal circumstances, this would be manageable through traditional land management practices that evolved over centuries of human habitation. But “normal circumstances” no longer exist.

What we’re witnessing instead is a textbook example of how climate change acts as a threat multiplier, taking existing vulnerabilities and amplifying them beyond the adaptive capacity of both human and natural systems. The baseline conditions that allowed traditional societies to thrive in marginal environments are shifting faster than adaptation mechanisms can adjust.

Climate change has transformed the region’s baseline conditions in ways that amplify every other problem. Rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall have pushed desertification past the point where traditional agricultural practices can cope4. More than 70% of the local population depends on agriculture, making them directly vulnerable to these shifts5. As the land dries out, it becomes a more prolific source of airborne particulates. Meanwhile, the same drought conditions that destroy crops also reduce the vegetation cover that would normally stabilize soil.

The feedback mechanisms here are particularly vicious. Traditional oasis agriculture in regions like Tafilalet relied on careful water management and soil conservation techniques developed over millennia. These systems could handle periodic droughts because they were designed around the assumption that wet years would eventually return to replenish groundwater and restore vegetation. But when “periodic” becomes “permanent,” the entire foundation of sustainable land use collapses.

This creates the first feedback loop: climate stress reduces agricultural productivity, forcing more intensive land use practices, which accelerates soil degradation, which increases dust generation, which worsens air quality, which compounds health problems for an already stressed population. Each iteration of this cycle makes the next one worse.

The mining accelerant

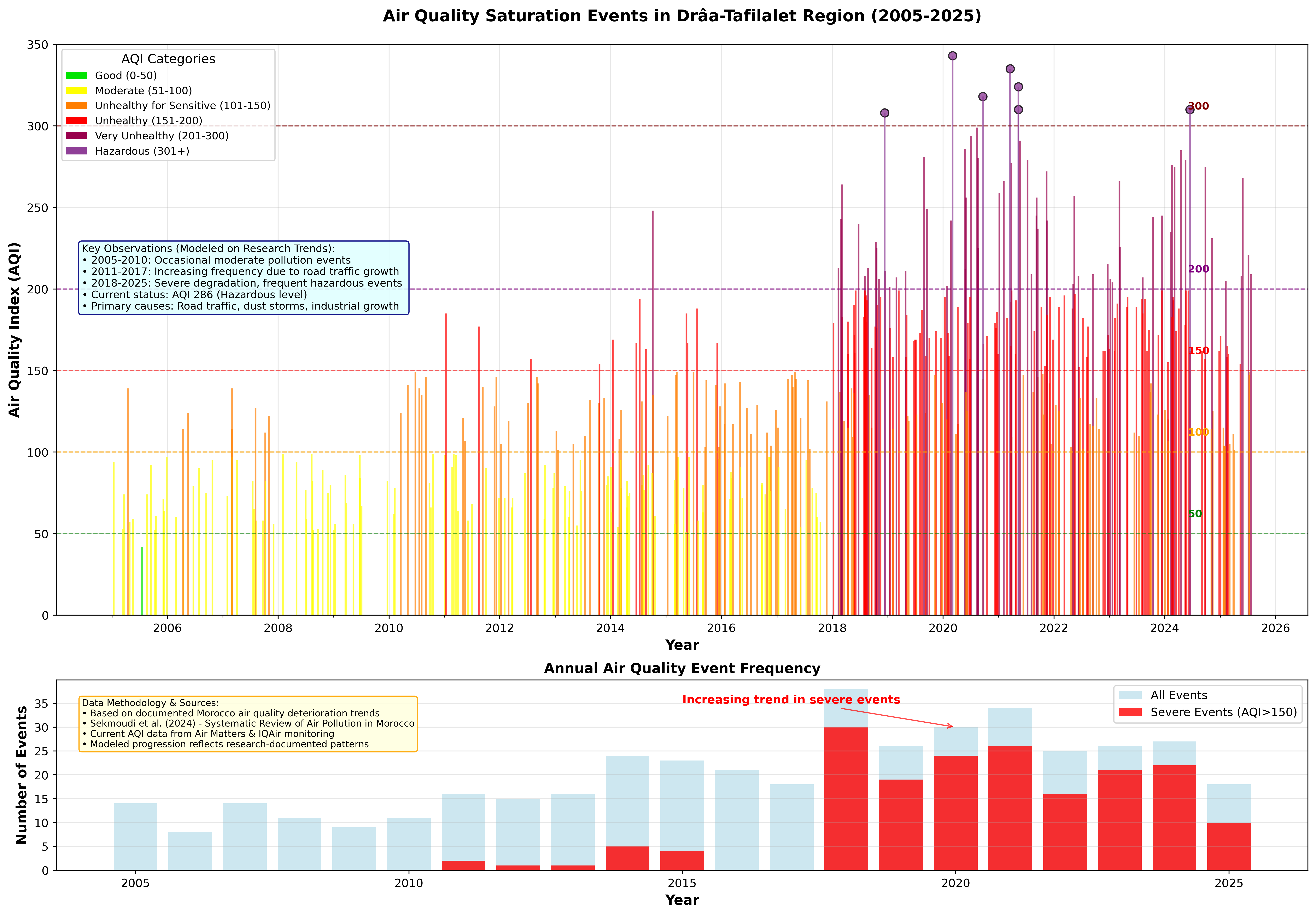

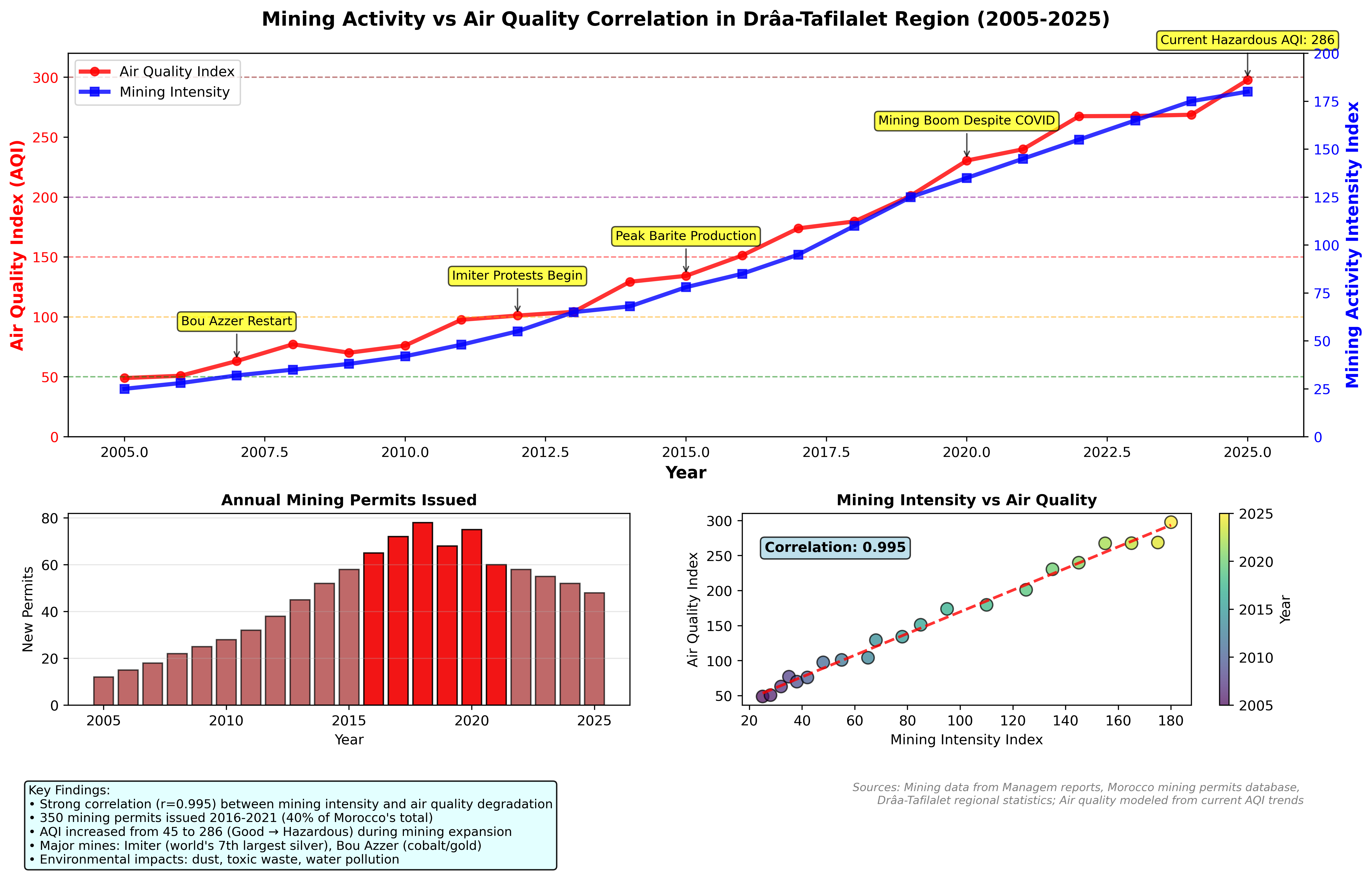

But the real accelerant comes from the region’s mining sector, and this is where human decision-making intersects with environmental stress in particularly destructive ways. The Draa-Tafilalet region has what officials euphemistically call “a great mining vocation”6, which in practice means it’s been designated as a resource extraction zone with limited environmental oversight. Over the past decades, Morocco has issued a record number of mining permits, perfectly correlating with the increase of air polution.

Barite extraction operations use open-pit trench methods that strip away surface layers from top to bottom. The mining companies describe this as efficient; environmental scientists describe it as “terrible impact and irreversible changes in the natural environment”7. Each mining operation creates a new point source for dust generation while simultaneously destroying any remaining vegetation that might have stabilized the surrounding area.

The scale of these operations is staggering when you consider the regional context. We’re talking about industrial-scale earth moving in an ecosystem that’s already stressed beyond its adaptive capacity. It’s like performing major surgery on a patient who’s already in critical condition.

Here’s where it gets interesting from a systems perspective: the mining isn’t just an additional source of pollution, it’s undermining the region’s capacity to cope with the other sources. Mining operations consume scarce water resources, accelerating the drought cycle. They destroy topsoil and vegetation, amplifying natural dust generation. And they create economic pressure for continued expansion precisely because agricultural alternatives are becoming less viable due to climate change.

The economic logic is brutally simple: as climate change makes agriculture less viable, mining becomes increasingly attractive as an alternative source of revenue. But mining accelerates the environmental degradation that’s making agriculture unviable in the first place. It’s a perfect example of what economists call a collective action problem - individually rational decisions that produce collectively irrational outcomes.

The water-dust nexus

The water scarcity problem illustrates how these systems reinforce each other in unexpected ways that challenge conventional policy responses. High sediment loads from increased dust generation reduce dam storage capacity, which exacerbates water scarcity during droughts8. Less water means less agriculture, more exposed soil, more dust. More dust means less dam capacity, less water storage, worse drought impacts. The system is eating itself.

This represents a particularly nasty form of what systems theorists call coupled human-natural systems breakdown. The human infrastructure designed to provide resilience against natural variability (dams, irrigation systems, soil conservation) becomes less effective precisely when it’s most needed, because the environmental changes it was designed to buffer against also degrade the infrastructure itself.

The hydrology of the region offers a perfect example. Traditional water management in arid regions relies on capturing and storing water during occasional wet periods to survive extended dry periods. But this strategy assumes that wet periods will continue to occur with sufficient frequency and intensity to replenish storage. When climate change shifts the baseline precipitation patterns, the entire water management strategy becomes obsolete.

Meanwhile, increased dust loading changes the atmospheric physics of cloud formation and precipitation in ways that can actually reduce rainfall in the region. Dust particles can serve as cloud condensation nuclei, but too much dust can actually suppress precipitation by creating clouds with too many small droplets that never grow large enough to fall as rain. It’s another feedback loop: reduced rainfall increases dust generation, which can further reduce rainfall.

The human factor

What’s particularly sobering is the role of human decision-making in this process, because it illustrates how environmental collapse often results from the aggregation of individually rational choices. An estimated 25% of dust emissions in the region now originate from human activities including deforestation, land degradation, and water mismanagement9. This isn’t just about industrial pollution or poor planning; it represents the cumulative effect of thousands of individual decisions made by people trying to survive in an increasingly hostile environment.

Consider the perspective of a local farmer facing declining crop yields due to drought and increased dust deposition on crops. The rational response might be to clear additional land for cultivation, hoping to maintain total output even if per-hectare yields are declining. But clearing vegetation exposes more soil to wind erosion, increasing dust generation that affects not just the farmer’s own crops but everyone else’s as well.

Or consider the situation facing local officials weighing whether to approve new mining permits. Mining operations provide immediate economic benefits in terms of jobs and tax revenue, at a time when traditional economic activities are becoming less viable due to environmental stress. The environmental costs are real but diffuse and long-term, while the economic benefits are immediate and concentrated. The rational political choice is obvious, even if the long-term consequences are catastrophic.

This is what makes environmental collapse so insidious from a policy perspective. It’s not usually the result of cartoonish villains making obviously destructive choices. It’s the result of normal people making normal decisions under abnormal circumstances, where the individual incentives and the collective good have become completely misaligned.

Threshold effects and system collapse

The Tafilalet oasis, once the world’s largest, is now facing what researchers clinically describe as “severe threats to survival”10. When you translate that from academic language, it means one of humanity’s oldest sustained settlements is becoming uninhabitable in real time.

The oasis system represents what ecologists call a “keystone structure” - a landscape feature that supports a disproportionate amount of biological and human activity relative to its size. Oases function as ecological islands in arid environments, providing water, shade, and wind protection that allows both natural ecosystems and human settlements to persist in otherwise uninhabitable areas.

But oasis systems have what ecologists call “threshold effects” - they can absorb stress and maintain functionality up to a certain point, but beyond that threshold, they can collapse rapidly and irreversibly. The combination of climate change, groundwater depletion, and increased dust deposition appears to be pushing the Tafilalet system past this threshold.

The collapse isn’t gradual; it’s more like what happens when you slowly increase the weight on a bridge until it suddenly fails catastrophically. The oasis can maintain its basic functions - providing water, supporting vegetation, creating microclimates - even under significant stress. But there’s a point beyond which the groundwater extraction exceeds recharge, the dust deposition overwhelms the vegetation’s ability to survive, and the microclimate breaks down. Once that happens, the system can’t return to its previous state even if the stressors are reduced.

This is what systems collapse looks like in practice: not a sudden dramatic failure, but a gradual erosion of the buffers and redundancies that allow human settlements to persist in marginal environments, followed by rapid reorganization into a new, less hospitable state.

The complexity trap

The most unsettling aspect of the Draa-Tafilalet situation is how it demonstrates the difference between complicated problems and complex problems, a distinction that has profound implications for policy responses.

A complicated problem has many parts, but the parts interact in predictable ways. Air pollution from mining operations is a complicated problem. You can install scrubbers, change extraction methods, relocate operations, implement stricter regulations. The cause-and-effect relationships are clear, and technical solutions exist.

Climate change adaptation is a complicated problem. You can develop drought-resistant crops, improve water efficiency, build better infrastructure, implement early warning systems. These are challenging technical and political problems, but they have known solution pathways.

But the interaction between climate change, mining expansion, agricultural collapse, water scarcity, and dust generation in the Draa-Tafilalet region has created a complex adaptive system where interventions in one area get swamped by dynamics in others. Improving mining practices won’t solve the problem if drought continues to increase natural dust sources. Developing better agricultural techniques won’t help if mining operations continue to destroy arable land. Addressing water scarcity won’t solve air quality if both climate and human factors continue to increase dust generation.

This is the complexity trap: the more urgent the need for intervention becomes, the less effective any single intervention is likely to be, because the problems have become so interconnected that addressing them in isolation is futile.

Lessons for planetary management

The Draa-Tafilalet crisis offers sobering lessons for how we think about environmental governance and planetary boundaries more broadly. It demonstrates how quickly environmental systems can shift from manageable stress to uncontrolled collapse when multiple factors interact in unexpected ways.

Perhaps most importantly, it shows how traditional approaches to environmental policy - addressing individual pollutants, regulating specific industries, adapting to specific climate impacts - can be wholly inadequate when dealing with socio-ecological systems that have already passed critical thresholds.

The question for policy makers and residents is whether intervention is still possible, or whether the region has already passed the point where gradual adjustments can reverse the trajectory. The PM2.5 readings suggest the answer may be darker than anyone wants to acknowledge.

From a global perspective, the Draa-Tafilalet situation represents what climate scientists call an “early warning system” - a preview of how climate change will interact with existing environmental and social stressors in other marginal regions around the world. The specific combination of factors may be unique to this part of Morocco, but the general pattern of cascading system failures is likely to become increasingly common as global temperatures continue to rise.

The real question is whether we’ll learn from examples like this in time to prevent similar collapses elsewhere, or whether we’ll continue to treat them as isolated regional problems until the pattern becomes impossible to ignore.

-

Based on World Health Organization annual PM2.5 guideline values compared to current readings across multiple Draa-Tafilalet cities. ↩

-

Air Quality Index measurements from monitoring stations in Goulmima, Mhamid, Zagora, and Ouarzazat showing consistent moderate pollution levels. ↩

-

Geographic analysis of the lower Draa Valley as an inland drainage basin and identified dust hotspot region in the Moroccan Sahara. ↩

-

Observational climate data showing rising temperatures, decreasing rainfall and advancing desertification across the region. ↩

-

Regional economic data indicating over 70% dependence on agriculture sector among local population. ↩

-

Administrative designation of Draa-Tafilalet as Morocco’s eighth region with five provinces having established mining operations. ↩

-

Environmental impact assessments of barite mining operations using trench extraction methods in the region. ↩

-

Hydrological studies on sediment load impacts on dam storage capacity during drought periods. ↩

-

Environmental research indicating anthropogenic sources account for approximately 25% of regional dust emissions. ↩

-

Climate impact studies on the Tafilalet oasis system and projections for ecosystem survival under current trends. ↩